|

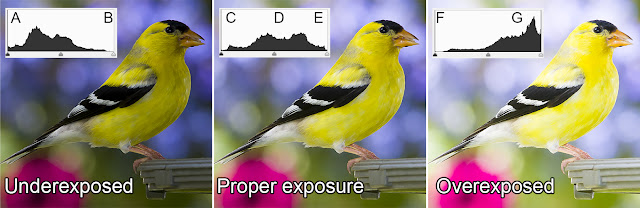

| Photos of a male American goldfinch; overexposed, properly exposed, and underexposed. |

As was mentioned earlier, the key to working with histograms is to pay attention to trends and not to get bogged down with the details. Notice the dark values for all three histograms (A, C, and F). There are a lot of darker values for the underexposed shot than for the overexposed one. The properly exposed image has some dark values, but they do not represent the majority of the scene. If the image was naturally dark with some bright areas it would be different, as you would expect to see a greater number of darker values.

The light values for all three histograms (B, E, and G) show a similar, although reversed, trend. There are very few light values in the underexposed shot, and way too many in the overexposed one. The properly exposed image has some brighter values, but really not too many. If this was an image with a lot of whites in it, such as a snow scene, I would expect there to be many bright values. However, in an average scene, there should not be such a pile up in that corner of the histogram.

The central histogram is properly exposed. Notice that there are few dark and light values and that the central portion of the histogram contains the bulk of the pixels. If you see bars of a histogram being shoved to one side or the other, especially with there being a flat, empty area on the other side, your image is very likely improperly exposed. How do you go about correcting this? That we will leave for another time.